The latest short-term outlook for US oil production published by the Energy Information Administration shows output rising to 13.2m barrels a day by the end of 2020. If this is achieved (and the EIA is traditionally cautious), the US will be the largest producer in the world.

The latest short-term outlook for US oil production published by the Energy Information Administration shows output rising to 13.2m barrels a day by the end of 2020. If this is achieved (and the EIA is traditionally cautious), the US will be the largest producer in the world.

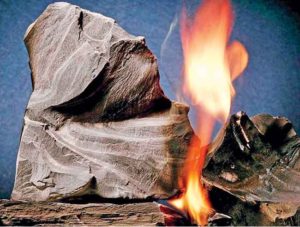

Two-thirds of that production will come from “tight oil” — that produced by fracking shale rocks. Ten years after the shale business began, the revolution is as dynamic as ever. Commentators who said shale was a marginal short-term phenomenon that would be killed off by falling prices, or rapid reservoir depletion, have been proved wrong. What began as a gas play now supplies the US with the bulk of its oil and gas needs.

Threatened by the downturn in prices after 2014, the shale industry has achieved a remarkable reduction in costs. The current outlook is for output to continue to rise until at least the mid 2020s even at current oil prices.

The impact on the global market and trade has been profound. The US is now a net exporter of both oil and gas, and recent figures from the International Energy Agency suggest that exports will continue to grow steadily. That means US production growth is absorbing most of the annual increases in global oil demand. US exports are also reshaping the world market for natural gas. The latest surge in gas exports, built on the growing volumes of that produced as a byproduct of oil extraction, is adding to a global glut. Prices can only fall further and expectations of a price surge in the early 2020s now look misplaced.

Shale gas has taken market share from coal in the US and despite the best efforts of the Trump administration the gradual decline of coal will continue. Shale gas has also undermined the US nuclear business.

Oil from shale has removed the US dependence on oil imports. Last year only some 1.5m b/d of oil was traded into the US from the Middle East, clearly reducing the strategic importance of an area that was once a priority for American foreign policy.

The revolution is live but has not yet been exported. The potential exists. There are shale rocks in China, southern Africa, Russia and many other places around the world. But progress has been slow, not least because additional supplies are simply not needed in a saturated market. Now, however, the situation is beginning to change. Shale development in Argentina and Canada is growing and the big energy companies, including BP and Chevron, are investing at a material level for the first time.

Source: “How the Shale Revolution is Reshaping World Markets”, Financial Times